5XB Football Broadcast

First Play-By-Play Football Broadcast

Made by Station 5XB in College Station

What follows is the full story of the first live radio broadcast of a football game. The broadcast was made on Thursday (Thanksgiving Day), November 24, 1921 from Kyle Field in College Station, Texas by amateur radio station 5XB. This information was found in a presentation by Mr. Frank Matejka (an operator at 5XU during the broadcast) that was stored in our club shack. This includes a photo of Mr. Tolson and Mr. Tolson's original letter on the subject, as appendix to the presentation.

- "The First Football Game Broadcast" written October 12, 1976

- Addendum

- Sidelights

- Equipment at 5XB - Texas A&M

- Equipment at 5XU - University of Texas

- Final Comments

- Sources of Information and Summary written November 3, 1976

- First College Football Broadcast written by W. A. Tolson around 1947

The First Football Game Broadcast

This publication was presented to the

MSC Radio Committee

W5AC

February, 1980 by:

Frank Matejka

THE FIRST FOOTBALL GAME BROADCAST

Texas A&M vs. Texas University

November 24, 1921

For some reason, sports-minded people, particularly broadcasters, seem to have suddenly become interested in the first football game broadcast and refer to it as some sort of legend or lore. This is not being fair because the facts have always been available to anyone who wished to know what they are. Several of the participants in this broadcast are still around and all have collaborated in furnishing the information which makes this narrative possible.

The broadcast was unusual -- it was accomplished by licensed radio amateurs using telegraphic code operating on amateur radio frequencies. The names of participants with licensed station call signs and hometowns were as follows:

- Harry M. Saunders, 5NI - Greenville, Texas

- George E. Endress, 5JA/5ZAG - Austin, Texas

- W. Eugene Gray, 5QY - Austin, Texas

- J. Gordon Gray, 5QY - Austin, Texas

- Charles C. Clark, 5QA - Austin, Texas

- Franklin K. Matejka, 5RS - Caldwell, Texas

Shortly after the hostilities of World War I ended, amateur radio activities began anew; and the students who had radio operating licenses were permitted to operate school stations. It was only natural that these operators would get together on more or less regular schedules; and it was during one of these exchanges between W. A. Tolson (now deceased), Chief Operator at Texas A&M Experimental Station 5XB, and operators at Texas University Experimental Station 5XU, that a decision was reached to undertake the transmission of the play-by-play activities of the forthcoming Thanksgiving football game from College Station.

At the time of the broadcast, the state of radio communications had not yet reached the point where vacuum tubes would be used in universal voice transmission; and instead, intelligence was commonly conveyed by dots and dashes using the International Morse radiotelegraph code. Transmissions by code are inherently much slower than by voice and its normal rate of speed is in the vicinity of 20 words or 100 characters per minute. This is too slow to keep up with gridiron activities and therefore, a system of abbreviations had to be devised. It so happened that Harry Saunders (now deceased) had previously worked as an operator with Western Union and was familiar with methods used by commercial telegraph companies in furnishing the play-by-play accounts of football and baseball games to newspapers, private sporting clubs, etc. When it was mentioned on the air to the operators at Texas University that such a list of abbreviations was being prepared, numerous requests for a copy of the list were received by radio and by mail from some of the 275 then licensed amateur radio operators in the state. Thus, what had started out to be a point-to-point broadcast, turned out to be one with many listeners.

For transmission, wires were run from the press box at Kyle Field to the station in the Electrical Engineering building a half-mile or so away. For reception, other wires were run to the home of a radio amateur who lived near the playing field. This arrangement enabled the operator to hear his own transmissions as well as those from amateur stations should their operators wish to interrupt for clarification or other information. The only radio equipment at the press box was a key for transmitting and a pair of headphones from receiving.

Although the reporting of play-by-play action in 1921 was simpler than that of today due to the absence of the two-platoon system and the lesser frequency of substitutions, it still required the help of spotters from each team to make it possible. The activity on the gridiron had to be put into abbreviations and then into radio signals. Actually, there was little delay in conveying the information to others and it is estimated that this delay rarely amounted to more than one play behind. Only one incident threatened the success of this broadcast. Near the end of the first half of the game a fuse blew out on the equipment, but this was hurriedly replaced by Tolson who went to the Electrical Engineering building after having been excused temporarily from his duty in the Aggie band.

It is doubtful that Saunders, the sole operator in the press box, ever envisioned the magnitude of the chore that he had agreed to accept.

The situation at Texas University was relatively simple; and with the exception of more persons in the room and the addition of an audio amplifier and horn speaker, it could well have been the location of another radio amateur listener. The Gray brothers (now deceased), Clark and Endress manned the transmitter and receiver positions, copying the abbreviations sent from Kyle Field and on occasion, communicating with Saunders. Slips of paper with received abbreviations were passed over a long table to Matejka, who relayed the decoding over a horn speaker through an open window to the many interested University students who had gathered outside to keep up with the progress of the game.

The broadcast was unique in another respect. It is safe to say that it is the only audience participation broadcast in which the members of the audience could converse with the master of ceremonies by means of their personal amateur radio stations.

The outcome of the game? It was a scoreless tie.

------------------------------------------

To make the story complete, it is planned to write an addendum to the preceding which would feature in detail the types of equipment which were used at both schools,

the preliminaries to the broadcast, people who were contributors to the broadcast but who did not participate and some human sidelights.

Only a few details remain to be either accepted or refuted.

------------------------------------------

F. K. Matejka

October 12, 1976

Addendum

The following is an addendum to the narrative of October 12, 1976, titled "The First Football Game Broadcast" and should be considered to be its extension and conclusion.

Mr. W. A. (Doc) Tolson, with a hometown of Sherwood, Texas, was a student in the Electrical Engineering Department, Class of 1923. He was a member of the San Angelo Club and a non-military member of the Aggie band. He was closely associated with the construction and assembly of radio station 5YA in 1920, which became 5XB a short time later.

Radio stations with call letters beginning with "X" were "experiment stations for the development of radio communication" which, among other things, permitted the use of higher power than those licensed with call letters beginning with the letter "Y" which were assigned to "Technical and training school stations".

A careful search of the government callbooks from 1913 through 1922 failed to show that Tolson had ever received an amateur radio station license with assigned call letters: however, in the early days, one could qualify and receive an operator's license only. The names of such licensees would not appear in government callbooks. He was, however, a code instructor in connection with Signal Corps training work. His close associate, Harry M. Saunders, Class of 1922, possessed an amateur radio station license, 5NI, as well as both Commercial First Class Telephone and Commercial Second Class Telegraph licenses. As best it can be ascertained, no other licensed operator was connected with the station.

It was thoughtful and appropriate that Mr. E. H. Elmendorf, Publicity Assistant at Texas A&M, wrote to Tolson in 1946 or 1947 requesting him to report the story on the football game broadcast. He made one serious mistake, however, when he included a date for the broadcast. In his reply, Tolson wrote, "Your letter states that the year was 1919. From my own memory I cannot recall the exact year...".

One can assume from the above that Tolson had some misgivings about 1919; otherwise, there was no reason for his having made special mention of it. He would have naturally had occasional difficulty in remembering details after some twenty-five years; but to change a date by two years during a four-year span of college attendance, he became faced with impossible irreconcilable situations. Neither station 5YA nor 5XB was in existence in November 1919; and although the former was in operation in November 1920, this was not a year in which the game was played at College Station.

Tolson deserves both sympathy and accolades for his efforts; and despite many discrepancies in his report, he furnished much information on many subjects which could be followed and put into proper sequence.

The dates of initial operation of both station 5YA and 5XB can be closely approximated from news items which appeared in QST (an amateur radio publication):

"College Station, 5YA, will be on as soon as school opens".

"... best work has been done by using station 5XB for relay, as all Houston stations can work this station at any time, day or night on low power".

By applying a time lag in publishing, it is apparent that station 5YA had a short life, most likely from September 1920 to about December 1920, at which time it was superseded by station 5XB. With this conclusion, station 5XU at Texas University never contacted station 5YA at College Station because 5XU was not in existence in 1920. The items also indicate that the station had been in operation for more than one year prior to the date of the broadcast.

Many press releases and stories have been written about the broadcast using various dates with corresponding scores, and it is not surprising that broadcasters and publications have continued to perpetuate errors which were inherent in any article based on the premise that the event occurred in 1919, written as if the date was 1920 and disregarding its actual date of performance in 1921.

From the tone of Tolson's report of the broadcast, one cannot help but wonder if its composition was not the result of much insistence by Mr. Elmendorf or others and that he did not relish its preparation. Why did he not establish the correct year before embarking on the narrative? Why did he choose the date of 1920 for the game when it is customary that Texas University plays Texas A&M at College Station only in "odd" years? Is it being "picky" to wonder why a college graduate writing a supposedly serious account of a happening for historical record would use such language as "I set out to build a ham transmitter that which there would be nothing whicher"?

Tolson's report forms the appendix to this narrative.

Sidelights

During the broadcast of the game a number of amateur radio operators called in on the frequency to ask for the score or for "fill-ins" on the reports. Even NKB, a hard-boiled Navy station at Galveston which occasionally complained of amateur radio station interference called in between halves to get the score.

There was an interesting report on the reception of the broadcast by William P. Clarke (now deceased) who at that time operated amateur radio station 5FB/5ZAF in Waco, Texas. Prior to the game he had with some difficulty persuaded the editor of a local newspaper to permit him to put his radio receiver in his office. The play-by-play received by Clarke was so far ahead of the Associated Press reports ordinarily furnished to newspapers, that the editor put a loudspeaker in a car and drove to the office of a rival newspaper where Associated Press reports were being given to a large crowd in the street. He advised the crowd that the play-by-play reports of the game as they occurred were being given at his office, with the result that most of the crowd rushed over to Clarke's installation.

Some of the details in this narrative have been verified by Cecil F. Butcher, 5AL, (now deceased), of Greenville, Texas, a real old-timer, whose early Navy training resulted in keeping a complete log of the broadcast as he received it. His log states in part:

"Thursday, November 24, 1921 -- cloudy and warm; up at 3 P.M. (he worked nights for the Katy railroad) and copy play-by-play report from 5XB of the Texas A&M ball game. 5XB comes in fine, no fading, and copy all of it without much trouble from his old buzz-saw rotary spark on 375 or 400 meters. Also 5XU very loud".

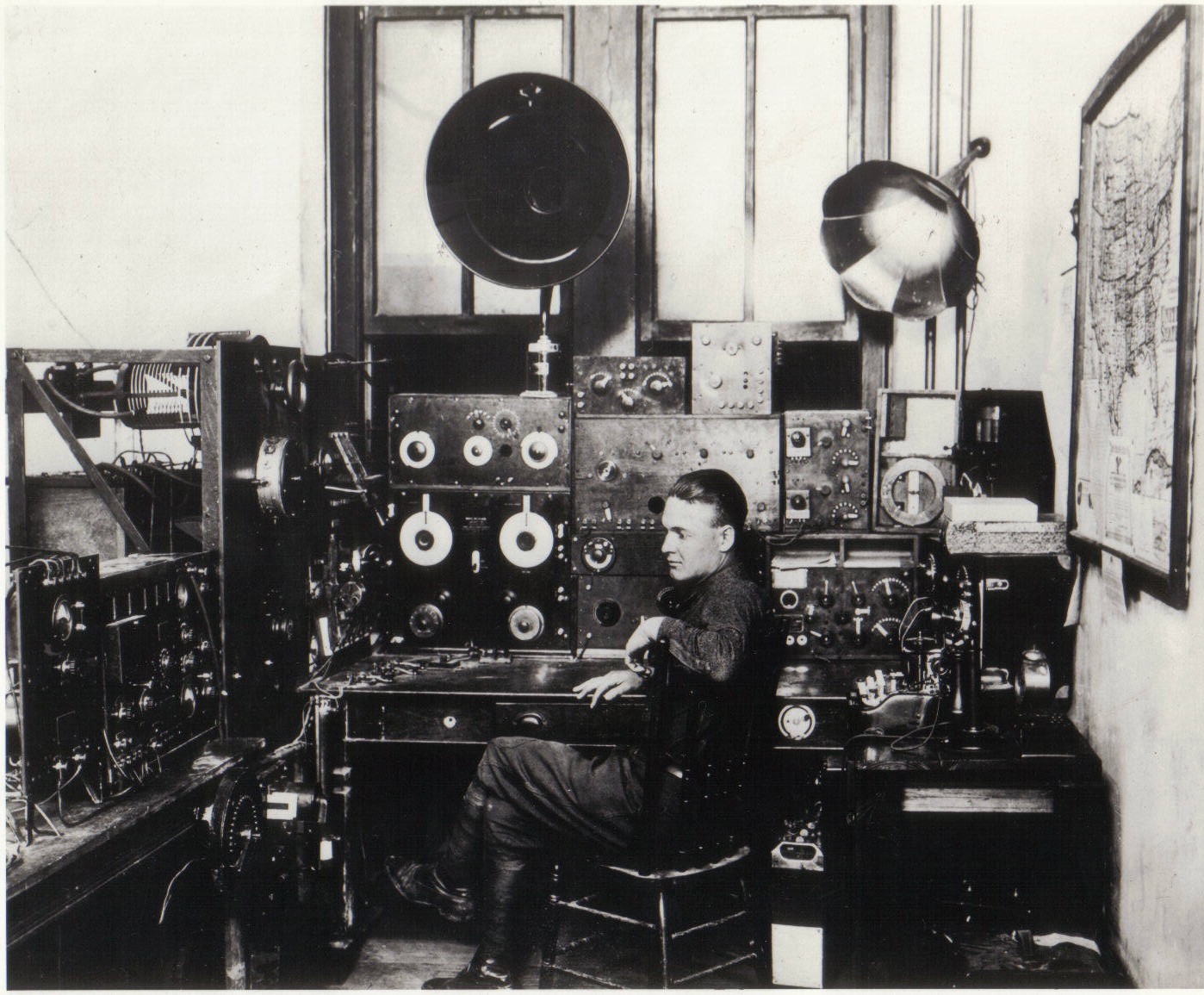

Equipment at 5XB - Texas A&M

The equipment was constructed for the most part in the Electrical Engineering laboratory by the radio amateur students interested in the station and with the help and guidance of the head of the Electrical Engineering Department, Dean F. C. Bolton who later became President of the College. The main power transformer had been constructed for oil testing purposes and was capable of providing the power limit of two kilowatts allowable under the special experimental license of 5XB.

The transmitting condenser consisted of about 100 clear glass photographic plates interlaced with tinfoil from damaged paper condensers from the laboratory. The entire "sandwich" of glass plates and tinfoil was immersed in an oil-filled copper-lined box. Its performance was unusually good considering the voltage involved.

The oscillation transformer was "loaned" by the Signal Corps Radio Laboratory which had been established on the campus during World War I for training of military personnel. It was a real beauty consisting of heavy aluminum wire wound on separators made from genuine mahogany.

A number of rotary spark gaps were tried from time to time and the one used on the date of the broadcast was a modified commercial unit bought by Saunders on radio row in New York City in the summer of 1921 while he was attending an R.O.T.C. summer training camp at Red Bank, New Jersey. The modification consisted of mounting the motor behind the control panel with its rotating shaft extended through the panel. The electrodes, both fixed and rotary, were then re-mounted on the front of the panel. A circular wooden cover with a glass front inclosed the gap forming an almost airtight unit. After a few characters were transmitted, the

...oxygen would be exhausted and the note of the signal neared that of a quenched gap. Near the end of each transmission, the operator would remove the power from the motor and its flywheel effect as the speed decreased provided a unique and distinctive signature.

The antenna was suspended from a steel tower on the Electrical Engineering Building in which the station was located on the third floor to another tower atop the dormitory next door. Details of its construction are not available.

The main station receiver was an early model Coast Guard tuner consisting of multi-tapped coils with both coarse and fine tuning taps supplemented by a variable air condenser. This tuning unit was connected to a World War I Signal Corps VT-1 vacuum tube detector unit and a two-tube audio amplifier. Filament voltage was obtained from Signal Corps alkaline storage batteries and the high voltage was provided by conventional "B" batteries. By today's standards such a receiver would be useless with crowded signals, but at that time it worked out fairly well.

The report of Tolson states that an amateur radio operator, the son of Professor H. E. Smith of the Mechanical Engineering Department, furnished the receiver for the broadcast. His home station was near Kyle Field and it was relatively simple to run wires from the receiver to the press box. A careful search of the callbooks of that period resulted in finding only one amateur radio station licensed to an individual with the surname of Smith who had a College Station address. The name and call letters were Ralph E. Smith, 5FA/5ZP.

Equipment at 5XU - University of Texas

The station was constructed and assembled in the Spring of 1921 in a World War I temporary building on 24th Street, just west of University Avenue. It was under the general supervision of the Physics Department and was the direct responsibility of Mr. George A. Endress, Resident Architect and Radio Director, father of one of the participants to the broadcast.

There were two spark transmitters -- one was a Navy Standard 2-KW Marconi with a quenched spark gap and the other consisted of a 1-KW Thordarson power transformer with a Navy type non-synchronous rotary spark gap. The latter gap had stationary electrodes on the outside circle and two electrodes on the rotor.

The antenna consisted of seven phosphor-bronze wires about 240 feet long on 20-foot spreaders, between two 110-foot steel poles. Because of poor ground conditions, the antenna was supplemented by a counterpoise about 20 feet longer than the antenna.

The receiver was a Grebe CR-2 which had a built-in two stage audio amplifier. This was connected to a Magnavox electro-dynamic speaker with a phonograph type horn.

Final Comments

This narrative is the result of much correspondence and research beginning with the first letter of inquiry to participants on November 18, 1962 (some 14 years ago). It can be said that in the interim an attempt has been made to check the complete accuracy of each detail to the greatest extent possible.

Probably the most debatable detail centers on whether Tolson participated in the actual broadcast. There is no question about his being involved in all of its preparations. In his report he does not say that he participated and neither does he say that he did not participate. Saunders, on the other hand, who was an operator in the press box, states that during the game he enlisted the aid of Tolson from the Aggie band to replace a fuse in the equipment at the station. Conclusion: Tolson did not participate.

A person who is not informed on communications matters may conclude that there might have been much scurrying around in making preparations for the broadcast. This is not true. The principal change at the station was to remove a high speed contactor (keying relay) and to substitute another which conformed to the voltage on the wires leading to the key at the press box. Such a relay is less than two inches square and would have cost not more than three or four dollars. The substitution would have been completed in a couple of minutes.

Headphones in quantity were available from the station as well as from code instruction classes. Twisted pair (two wires twisted together) has continued to be available in long lengths on large spools or reels for the connection of various electrical devices which use relatively low voltages. The maximum effort expended on the preparation for this broadcast would most likely have been the stringing of the twisted pair while making temporary attachments to poles, buildings, trees and the like from the press box to both the transmitter and the receiver. Only part of a day would be required to accomplish this work.

Many of the references made in the report to individuals who assisted in the assembly of the station actually occurred in 1920, more than a year prior to any thought of the broadcast; and, as such, in the mind of the writer, are not relevant to this accounting.

Sources of Information

-

Callbooks "Amateur Radio Stations of the United States"

Dept. of Commerce, Bureau of Navigation - 1913 through 1922. -

QST magazine - 1920 through 1922.

-

James L. Lindsey, Director, College Information and Publications, Texas A&M - 1963.

-

The Longhorn - 1921 and 1922.

| Butcher, Cecil F. | Gray, W. Eugene |

| Clark, Charles C. | Saunders, Harry M. |

| Clarke, William P. | Tolson, W. A. |

| Dillingham, H. C. |

Summary

DATE: November 24, 1921 (Thanksgiving Day).

EVENT: Football Game.

LOCATION: Kyle Field, College Station, Texas.

TEAMS: Texas A&M vs. Texas University.

OUTCOME: A scoreless tie.

BROADCAST: Point-to-point (Principally).

BY WHOM: Licensed amateur radio operators.

HOW: By International Morse radiotelegraph code.

TRANSMITTING: Station 5XB, Texas A&M.

IN CHARGE: W. A. Tolson.

OPERATOR: H. M. Saunders.

RECEIVING: Station 5XU, Texas University

IN CHARGE: G. A. Endress.

OPERATORS: C. C. Clark; W. E. Gray; J. G. Gray; G. E. Endress; F. K. Matejka.

- F. K. Matejka

November 3, 1976

First College Football Broadcast

Texas A&M - University of Texas November 25, 1920

by W. A. Tolson

Engineer RCA, Princeton, New Jersey

The question you raise as to the first broadcast of a football game has come up several times before, but heretofore stress of circumstances made it very difficult to take the time to dig up and present all the information at my disposal. However, I am going to attempt to lay this ghost once and for all if at possible. Accordingly, I have dug out my old notes on the operation of old 5YA (predecessor to 5XB and WTAW), my photo album, and have cudgeled my memory as to the events leading up to the broadcast which (at the time) we considered as only a stunt, but which now appears to have some historical significance.

In starting the chain of circumstances, I am forced to point an accusing finger at Dr. F. C. Bolton, who at that time was Professor of Electrical Engineering. He was guilty of permitting (nay, even encouraging) me to become so thoroughly inoculated with the germs of Radio that even at that time my case was practically hopeless. During the war he had exposed me to the infection by putting me in the code room as an instructor, and having me operate the spark transmitter, which was used in connection with the Signal Corps training work.

As soon as the war was over, and radio was permitted to civilians on a "ham" basis again, I set out to build a ham transmitter than which there would be nothing whicher. In this I was aided and abetted by my partner in crime, B. Lewis Wilson. At that time Lewis was in charge of electrical maintenance in the E. E. Laboratories. Lewis supplied a tremendous amount of initiative, self-confidence, and drive, all three of which I lacked. I believe Lewis is now in the electrical contracting business in Denton. His recollections on the subject may be valuable.

Our first step in building the Rock Crusher transmitter was to "steal" from Prof. O. B. Wooten's testing laboratory a high-voltage transformer, which had been built by the students in the two-year course for electricians, for oil-testing purposed.

The oscillation transformer was "swiped" from the Signal Corps Radio Laboratory. It was wound with aluminum wire, and insulated with BEAUTIFUL mahogany.

The transmitting condenser was easy. We had only to "procure" about a hundred glass photographic plates from the Campus Photo Studio, secure (by night) a copper-lined box from Prof. Wooten's laboratory, and unwind a few tinfoil-paper condensers from the same source. After all, the condensers were no good, having been accidentally damaged beyond repair. After assembling the glass plates and tinfoil in the copper-lined box, it was filled with oil (source unidentified). Thus the shining countenance of many a former student gazed complacently through the murky depths of the oil in our coffin-like condenser.

The rotary spark gap was a little more difficult. In Prof. W. G. James's office was an object which made our mouths water. It was an electric fan with a beautiful overgrown motor. However, the progress of science was somewhat delayed by the adamant refusal of Prof. James to allow his fan to be placed in winter storage until the weather got cool. If my memory does not play tricks, fate intervened in favor of science. It seems that the fan accidentally fell out of the window, where it had been carelessly placed by someone. When the fan was retrieved from the sidewalk, it was found that the blades were hopelessly damaged. There was no reason, however, why the motor could not serve a useful purpose as the prime mover for a rotary spark gap.

All the above items may be identified in the accompanying photograph, which I hope you will return as it ranks high in my meager list of possessions.

Thus was born the original rock-crusher ham transmitter at A. and M.

Dr. Bolton fought for and secured a transmitter license for the station which carried the call letters 5YA. The "Y" at that time designated an educational institution. Later the letter "X" was used to designate an experimental station, and the call letters were changed to 5XB.

In order to localize the radio infection as much as possible, Dr. Bolton set quarantine limits on a small room at the end of the hall on the third floor of the E. E. building. With the "equipment" installed, and an antenna swung from the roof of the E. E. building to the old tower atop the dormitory next door, there was foisted upon the then small and select Radio Fraternity one of the worst sources of interference known to the art at that time. (I shudder to think how many kilowatts Wooten's oil-testing transformer may have drawn from the line.)

I cannot recall at just what point Harry M. Saunders (E.E. '22) entered the picture. Harry was by far our best operator, having had considerable experience as an A. P. operator, and he had a beautiful "fist". He was an enthusiastic ham, and we sat out many a watch together until the wee sma' hours when we got tangled with a real DX station.

There was another man who also assisted in the operation of the station at that time, and who cooperated throughout in planning and executing the broadcast. Cudgel my memory as I will, I cannot recall his name. If any publicity is ever given to the subject broadcast, I hope that an opportunity will be given to this man to make himself known. I feel that he is due my abject apologies for having paced him in an embarrassing position on account of my faulty memory. (Try R. G. Eargle, E.E. '24. He many be the man.)

Now as to the actual broadcast. Your letter states that the year was 1919. From my own memory I cannot recall the exact year, but the game was definitely the Thanksgiving game with TU. Here is how the idea originated.

We had been operating 5YA for some time as a typical ham relay station. We received so many requests from stations throughout the Southwest that we agreed to get on the air immediately after the Thanksgiving game and give them the score. Then the idea began to grow that it would be swell to give them a play-by-play account of the game. Unfortunately there were two difficulties. First, we had no way to control the transmitter from Kyle field, and, second, Morse code would be so slow that we would not be able to keep up with the game.

In overcoming the first difficulty, it was a simple matter to run a twisted pair from the E.E. building to Kyle Field, but to handle the primary current of the transmitter over such a line was another matter. As usual, Dr. Bolton came to the rescue when we were in trouble. He appealed to the Signal Corps, who still had at least a paternal interest in our establishment, and they came forward with a high-speed contractor which sounded like the clatter wheels, but which served the purpose admirably.

The difficulty with the time element was solved by a plan which I believe was proposed by Harry Saunders. We would simply make up a list of abbreviations which would be used during the broadcast, and mail a copy to any of the amateur stations who were interested in receiving the broadcast. The abbreviations went something like this: if we sent "TB A 45 Y", the interpretation would be "Texas's ball on the Aggie's 45 Yd. line". If we sent, "T FP 8Y L", the interpretation would be "Texas forward pass 8 yards loss". The idea was very simple, and worked beautifully, as the results of our transmission later proved. We accordingly went into a huddle and worked out a list of abbreviations with one of Coach Bible's assistants. We then took the bull by the horns and ran off a couple of dozen copies to mail to anyone who was interested. We then began mentioning, to such hams as we thought would be interested, that the list was available for the asking. The result was rather astounding. Apparently the information was passed around "by word of spark" and we deluged with relay messages from stations we had never heard of, asking for the list. Overnight we were doing a land office business. We ground the mimeograph until our arms ached and we licked envelope flaps until I can still taste it. I suspect that Dr. Bolton's stamp budget was overexpended for the next three years!

Some time ahead of the big game, we ran the twisted pair down to Kyle Field and tried out the control system. Electrically, it operated perfectly, but we ran into a psychological snag. The operator could not hear what he was sending, and therefore had no "feel" of his key. His sending was terrible. At this point we received help from an unexpected source. Prof. Smith, of the mechanical engineering department, lived immediately adjacent to Kyle Field. His son, in high school, was also a dyed-in-the-wool ham. I must apologize that I cannot recall the son's given name. At any rate, Prof. Smith's son came forward with the suggestion that he had a good receiver in operation, and it was only a stone's throw to Kyle Field. Why not run a twisted pair from his receiver to the press box, and give the operator a pair of phones so that he could hear what he was sending? No sooner said than done, and we found that the setup was perfect. Not only was our problem solved, but we found that we were collecting dividends which we had not anticipated. In those days of high-decrement transmitters and low-selectivity receivers, you could turn on your receiver and hear practically any station on the air without bothering to tune your receiver. We found that we had a perfect break-in system. During the actual broadcast of the game, several "ham" stations called in between quarters and halves to ask questions. Even NKB at Galveston (a hard-boiled station if there ever was one) called in between halves to get the score, as he had been busy with traffic and had lost track of the game.

Credit for outstanding performance in the reception of this broadcast should go to W. P. Clarke, who at that time operated station 5ZAF in Waco. He had to argue mightily to get permission to install his receiver in one of the local newspaper offices. Apparently they had no confidence in this "amateur radio stuff", but were willing to humor them. The report we got from Clarke after the game was to the effect that our reports were so far ahead of A.P. that at the end of the first half his newspaper put a Magnavox loud speaker in a car and drove down to the rival newspaper office where they were giving out the A.P. reports to tremendous crowd in the street. They announced to the crowd that they were giving out play-by-play reports AS THEY HAPPENED. The result was a near riot in front of Clarke's installation.

The above is, to the best of my knowledge, a fairly accurate account of the events leading up to the first broadcast of a football game from station 5YA. I also suspect it was the first such broadcast in history. Before sticking you neck out too far, however, I would suggest that you get in touch with the other people I have cited, if it is possible to do so. In this way you will have a four-way check on my memory, which is rather hazy on some points after 27 years.